🎞️ The Shawshank Redemption (1994):

Stonewall, Dignity, & The Discipline of Hope

I’m still mildly offended on behalf of 1994.

Not because Forrest Gump won Best Picture (I love Forrest Gump—a warm, guileless epic that somehow manages to be both a hug and a history lesson). But because The Shawshank Redemption didn’t. The 1995 Oscars honoured one of the most classic-stacked years on record—rounding out Best Picture were Pulp Fiction, Quiz Show, and Four Weddings & a Funeral—and the statue went to the film that best matched the national mood, ignoring the one that would quietly outlast the entire ceremony. Shawshank was nominated for seven Academy Awards and won zero. And yet it prevails as both one of the greatest and most popular films ever made.

Which is, honestly, the most Shawshank thing imaginable: the institution gets the paperwork wrong; the truth survives anyway.

I first saw Shawshank on its initial UK release in February 1995, aged 18. I was in my first year of film school and—of course—already film-nerdy, already learning to talk about movies as if they had skeletons and circulatory systems. I saw it in the cinema with my first boyfriend, John, and I loved it in a late-teen way: clean, broad-stroke, morally satisfying.

Innocent man. Unjust system. Perseverance. Friendship. Triumph.

Three days ago I watched it again, this time on the sofa with my mum—her first time, my… well, let’s call it “a well-established tradition”—and she absolutely loved it. That mattered more than I expected because it reminded me why the film works before it works as metaphor. It’s a beautifully told story. It’s tight without feeling rushed, patient without feeling slack. It’s one of those films that can hold a first-timer and a compulsive over-analyzer in the same scene and satisfy them both.

And then came the opera.

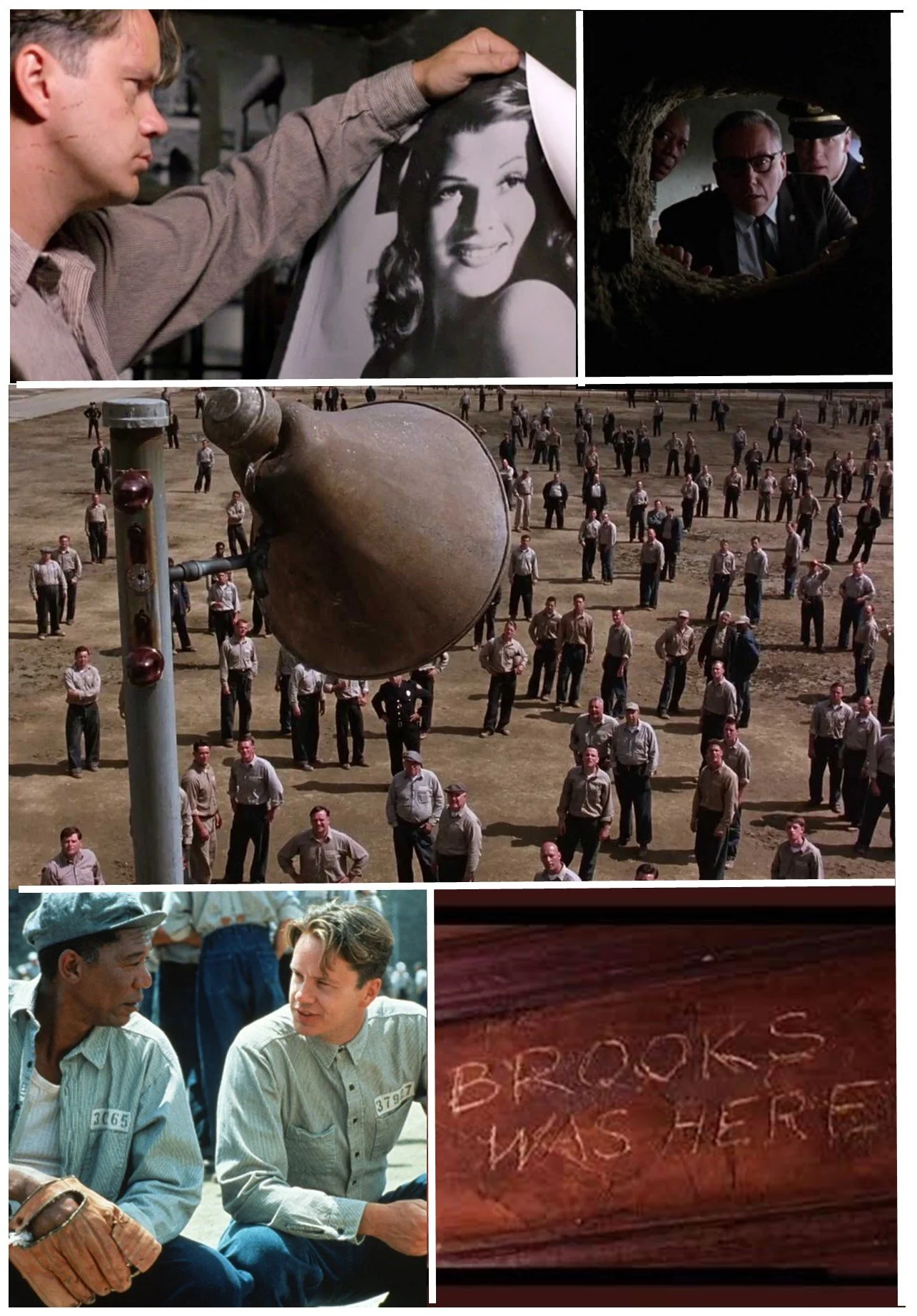

Andy plays Mozart over the prison loudspeakers—two women singing like the sky has cracked open—and for a minute the institution pauses, confused, briefly outmatched by beauty.

My mum had tears in her eyes. Then she said, completely deadpan: “Oh… all that choice—he could have played some rock and roll for them.”

I laughed. And then I realised she’d accidentally nailed the scene. Because the point isn’t what he plays. It’s that he chooses anything at all in a place designed to strip choice from your body, your time, your language, your future.

I watched that moment at 18 and thought: that’s inspiring.

I watched it now and thought: that’s uprising.

The Rebellion You Inherit vs. the Rebellion You Earn

I don’t think you can fully understand rebellion until you’ve lived your own war. When you’re young, rebellion can be something you inherit as culture. You recognise it before you fully feel it. It comes as symbols and stories: the French Revolution as spectacle—crowds, slogans, the intoxicating idea that an order can be toppled. Punk as mythology—noise, refusal, a middle finger raised at whatever the adult world calls “normal.”

Stonewall belongs in that lineage too, but it carries a different charge. Not aesthetic. Not theoretical. Not something you admire from a safe distance.

Stonewall is dignity turning into refusal. It’s people who were being policed, shamed, criminalised—told by institutions that they were wrong, sinful, deviant—saying, collectively: We are done being managed. We are done apologising. We are done disappearing. We exist.

And what connects Stonewall to Shawshank—what makes it more than a historical reference for me—is the tension between dignity and institutional control.

Institutions at their most insidious don’t merely restrict behaviour; they define humanity. They decide what version of you is acceptable. They don’t only build walls; they build scripts. They attempt to author your life in advance and then punish you for improvising.

Stonewall was improvisation. It was refusing the role the system had written.

And adulthood—maddeningly—delivers your wars in admin fonts. Not with guillotines or guitar feedback, but with policies, metrics, “best practice,” and the slow bureaucratic pressure that tries to make you smaller while insisting it’s for your own good.

That’s when rebellion stops being a style and becomes a practice.

That’s when Shawshank stops being “just a favourite movie” and starts being a mirror.

Institutionalization: The Real Horror

Yes, the film shows violence. But the deeper horror isn’t the bruises.

It’s the normalisation.

Shawshank is a machine designed to convert a person into something manageable: a number, a routine, a unit. Over time it doesn’t just contain you. It teaches you what to expect. What not to ask for. It trains your nervous system to live inside a cage—even when the door is open. And that concept is felt brutally when the character of Brooks - softened by over 50 years of incarceration - is finally released. Despite a program designed to reintegrate him into society, the overwhelm at being thrust back into a world he simply doesn’t recognise causes him to make the desperate decision to end his own life. It’s a devastating moment, not least because the film has already questioned the validity of life sentences for young men who have drifted.

Brooks’ arc is the warning label. Not because it’s “sad,” but because it’s what institutionalisation looks like when it works as designed: the institution becomes the only world the person can safely inhabit. Freedom becomes disorientation.

And once you’ve lived long enough, you can’t unsee the bigger truth: institutionalisation isn’t limited to prisons.

It happens in workplaces. In healthcare. In government. In “ordered” society. In organisations that start with a mission and end with a machine. Anywhere “this is how we do things” becomes more important than “this is why we exist.”

Which is why the film feels so current now. Institutions everywhere are getting bolder about what they want from us: compliance, obedience, silence, a smaller life. We are watching the re-rise of fascism in real time. And let’s name it plainly: white nationalism and white Christianity, wielded as identity and weapon rather than faith, are being used—especially in the U.S.—to launder cruelty into righteousness. It’s not subtle. It’s the warden’s Bible with a Presidential Seal and a camera crew.

The Warden: Virtue-As-Cover, Power-As-Business

At 19, the warden was “the corrupt bad guy.”

Now he reads as a specific, recognisable modern type: the moral manager. The values performer. The man who understands power isn’t only enforced—it’s marketed.

He wraps control in righteousness. Uses religion as prop. Leverages the ‘wrongness’ of convicted criminals to posture a morally superior stance. Performs virtue while laundering money. The film is unblinking about what that means: corruption doesn’t only happen in shadows. It happens under fluorescent lights, behind a story called “good order.”

He doesn’t just want to control the prison. He wants to be applauded for controlling it. Now there is a mirror to modern global leadership.

Paperwork Rebellion, or: The Most Adult Thrill in the Movie is a Library

There’s a stretch of Shawshank that is essentially administrative competence porn: letters, budgets, books, forms. It’s weirdly exhilarating, which is how you know you’re not 19 anymore.

When you’re young, rebellion is loud. It’s chaining yourself to a fence. It’s shouting. It’s chaos.

When you’re older, you realise the most effective rebellion is often infrastructural. It’s leverage. Persistence. Finding the seams in the system and working them until they yield.

Andy becomes fluent in the levers behind the wall. He learns the language institutions respect—finance, legitimacy, paperwork—and he uses it to build something human inside something inhuman. The library isn’t a nice subplot. It’s a parallel system. A long-form insurgency.

And this is where my professional brain always catches on that phrase I hear constantly in leadership and nonprofit worlds:

Hope isn’t a strategy.

I’ve heard it. I’ve nodded along to it like a bobblehead in meetings. I’ve said it myself.

And sure: hope without plan is just vibes. Hope without action is a scented candle.

But Shawshank argues something sharper. Hope isn’t a strategy by itself. Hope is a facet of one. Because for Andy, hope isn’t a wish. It’s method.

Hope as Disciplined Practice

If hope means “it’ll all work out,” then no—hope isn’t strategy. That’s denial with better PR.

But Andy hopes like an engineer.

He builds hope into routine. Into time. Into redundancy.

He writes letters for years—not because he’s manifesting, but because he understands institutions fatigue. Attrition. Persistence as leverage.

He protects an interior world—music, books, chess, rocks—not as escapism, but as defence against spiritual colonisation.

He makes himself useful without surrendering himself. He plays the long game in a place designed to erase the long game.

Hope, in Shawshank, isn’t a mood. It’s architecture.

And if you’ve ever tried to “practice what you preach” inside a system that rewards performance over substance, you know how radical that is. Because “living your war” is exactly that: refusing to be a virtue. Refusing to become the glossy version of yourself institutions find convenient. Walking the walk when it would be easier—and often more rewarded—to just keep talking the talk.

Red’s Arc: The Real Escape Isn’t the Tunnel

Here’s the sneaky truth: Andy’s plan is the plot, but Red is the transformation. A recurring motif in the film is Red attending parole hearings that occur every few years. He says the right words about being rehabilitated, shining a light on what remans the biggest joke of the modern prison system - that there is any intention or effort at rehabilitation. His parole is denied every time.

Red is what institutionalisation looks like once it’s settled in: competent, resigned, quietly brilliant at surviving a cage. He doesn’t posture. He doesn’t pretend. He’s learned the rules so well that freedom starts to sound irresponsible.

That’s why the parole hearings are so brutal. “Rehabilitated” isn’t a state of being—it’s a performance. A script you’re meant to recite. Red tries the script, fails, tries again. And eventually, he stops performing. Not because he doesn’t care, but because he refuses to fake it. And when he does - that parole is granted.

And slowly—painfully—Red has to do something harder than dig a tunnel: he has to accept the risk of hope. Not the mood version. The practice version. The version where you step forward before you’re sure the ground is there.

There are agonising moments as Red treads the path that Brooks walked before him. We are convinced he will fall to the same fate. But in one of the film’s most stirring and quotable lines, Red (with the ever-guiding hand of an omnipresent Andy) has to decide to ‘Get busy living, or get busy dying’. And then we are en route to one of the most thrillingly satisfying endings in cinema history.

That’s the real jailbreak of the film: not leaving prison, but leaving the prison inside you.

The Opera Scene: Dignity Forced Into the Institution

The opera scene - when Andy barricades himself in the warden’s office and plays Mozart over the prison’s entire loudspeaker system - is the film’s spiritual centre. It doesn’t fix the system. Andy is punished. Badly. The machine snaps back.

But for one minute, the institution is forced to host a beauty it did not approve. That’s Stonewall energy—not in aesthetics, in principle. The assertion that the institution doesn’t get to define what is human, what is worthy, what is allowed to be felt. For that minute, the prison is not the author. Andy is.

(And yes—my mum is right. A rock and roll tune here would’ve slapped. But maybe the point is he chose something unplaceable, uncontainable. A sound from outside the script. It also continues to reveal more and more of who Andy is as a person.

The Masterpiece Part: The Storytelling is Ridiculously Tight

Themes aside, Shawshank is also just a masterclass in storytelling. There are precious few films I would put into this category of exemplary, ‘no fat’ narrative.

The editing is elegant. The pacing is patient but never slack. Every scene either lays track or pays it off. Morgan Freeman’s iconic narration—rarely done this well—doesn’t smother; it becomes the film’s rhythm, its tenderness, its fable-like inevitability. The score knows exactly when to lift and when to disappear. The leads and ensemble are sublime. And the cinematography—probably my favourite aspect of this film—earned a first-time Oscar nomination for cinematography legend Roger Deakins (who finally got his Oscar glory in 2018 and 2020, for Blade Runner: 2049 and 1917, respectively).

And then the film does what the best films do: it makes you think you’re watching one kind of story, and later you realise you’ve been watching another.

Which brings me to the moment that still gives me chills:

The warden throws the rock.

It punches through the poster.

And you hear it—the rattle, the hollow run, the tunnel answering back like a drumline from years ago.

In one brutal, perfectly timed beat, the movie reveals itself as a slow-burn heist that’s been happening right beside us the whole time. It doesn’t need to scream “SURPRISE.” It lets sound do the work. It lets the tunnel—patient, absurd, heroic—stand as proof.

That’s the joy of great storytelling: the truth was there all along, and the pleasure is recognising how perfectly you were led to it.

My Personal ‘Poster Moment’

That “poster moment” hits me now because I’ve had my own version: the instant you realise there’s a tunnel behind the story you’ve been telling yourself.

For me it was my two-year stint working in India with the contact centres. Before that, my big flashy job was in the UK. Going to India made people in the UK redundant and gave people in India jobs—and for a while you can tell yourself the poster story: global opportunity, efficiency, better customer outcomes.

But behind the poster was the tunnel: low-balling because it was cheap, terrible working conditions, cultural humiliation, human beings turned into throughput, values turned into slogans. That was the moment the rock went through for me. I heard the rattle. I couldn’t unhear it.

It was the point where I realised I couldn’t stay in that sector—not because ambition is evil, but because I didn’t want to become institutionalised into a system where my job was to make harm more efficient.

That was also, in a strange way, my move toward freedom: stepping into nonprofit not because it’s perfect (it isn’t), but because it offered a better chance to be myself—values and all—without having to perform virtue inside a machine that treated virtue as branding.

Why it Endures

My mum loved Shawshank because it works on universal terms: friendship, resilience, injustice, catharsis, the satisfaction of a moral ledger finally balancing.

I love it because it’s all of that, and because it’s a film about how power works, how institutions shape people, and how resistance often looks like quiet practice.

And yes: the world has gotten itself in a hurry. Institutions feel sharper-edged. Fascistic impulses are being handed microphones and uniforms and scripture. White nationalism is being normalised in plain sight. Values are performed while cruelty continues uninterrupted.

In that environment, “hope isn’t a strategy” becomes a tempting line people use to sound serious.

But Shawshank offers a better correction:

Hope isn’t a strategy by itself.

Hope is the part that makes strategy possible. The part that keeps you building the library when the system would prefer you numb. The part that keeps you writing letters when the timeline is absurd. The part that refuses to let the institution colonise your interior world.

For a movie set almost 100 years ago inside the prison system, The Shawshank Redemption remains a surprisingly relevant film—and this rewatch only reasserted its position as an all-time great.

Synopsis:

The Shawshank Redemption follows Andy Dufresne, a reserved Maine banker sentenced to life at Shawshank State Penitentiary for the murder of his wife and her lover—a conviction he insists is wrong. Inside the prison’s harsh routines, Andy forms an unlikely friendship with Ellis “Red” Redding, a long-serving inmate who knows how things work and how to get by. As the years stretch into decades, Andy quietly reshapes his corner of Shawshank—earning trust, clashing with authority, and building a reputation for patience and ingenuity—while Red watches, narrates, and slowly changes alongside him. It’s a gripping, steadily unfolding story of endurance and friendship, with one of cinema’s most satisfying long-game payoffs.

🎬 Mise en Scène: Era Notes:

Year of Release: 1994

Cultural Context: Mid-’90s America was deep in “tough on crime” politics and moral posturing — the era of mass incarceration, the War on Drugs hangover, and institutions insisting they were righteous while grinding people down. A country newly post–Cold War, but still obsessed with control, punishment, and who gets to be “redeemed.”

Era Peers: The Fugitive, Dead Man Walking, A Few Good Men, Quiz Show — stories about justice systems, public virtue, and the gap between what institutions claim and what they do.

The Vibe: Patient, humane, deceptively classical. A slow-burn fable that moves like a heist, feels like a sermon, and lands like a release of breath you didn’t know you were holding.

Why It Matters: Because it isn’t really about prison — it’s about institutionalisation, and the quiet rebellions that keep a person human. Proof that hope isn’t naïveté; it’s discipline.

🎬The Director’s Cut:

First Watch: UK cinema, February 1994

Rewatch: With Mum, in Canada, on digital, 2025.

Scene that Still Gets Me: SO MANY! The ‘poster reveal’ has to take the crown, though.

Will Be Remembered For: Being the number one movie on IMDb’s ‘Best Movies’ list for over 3 decades. Being the most overlooked Oscar-nominee ever (7 nominations, zero wins, now a modern classic)

Re:Cut Verdict: A slow-burn masterpiece that disguises itself as a comfort watch, The Shawshank Redemption doesn’t just tell a story about wrongful imprisonment—it maps how institutions grind people down, how power launders itself as virtue, and how a person can survive without surrendering his inner life. It’s also filmmaking at its most elegant: patient pacing, immaculate structure, perfectly-timed reveals, and Morgan Freeman’s narration doing the rare thing narration almost never does—making the story feel bigger, warmer, and more inevitable. By the time that rock hits the poster and the tunnel answers back, you realise you weren’t just watching an escape plan. You were watching hope built, piece by piece, into a strategy for staying human.